Think of a carriage for a queen and many would imagine the regal glamour of Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee State Coach pulled by six horses, making its way along The Mall glistening with gold trim. As John Wright discovers, the Queen in this story had a different reason for approaching the Kinross family.

The Kinross Carriageworks was a dynasty of coach builders in Stirling, central Scotland stretching from 1802 to 1966. “From the mid-18th Century, Stirling became one of the principle centres of Coach Building in Great Britain.

In 1865 the Bastion [‘Thieves Pot’ or Bottle Dungeon’, once part of the defensive Burgh Wall] housed a forge as part of Kinross’s famous Carriage Works,” an inscription appearing in the city’s Thistle Shopping Centre proclaimed. They also made the first two-seated gig in Scotland.

Stirling is 26 miles north-east of Glasgow and 37 miles north-west of Edinburgh. Once a medieval market town surrounded by rich farmland and dominated by Stirling Castle with the strategic advantage of having a bridge over the River Forth and a port, it has often been called the “Gateway to the Highlands”.

Roads were once not much to write home about, a 1669 law requiring a mere six days labour a year to be spent on road maintenance! A century later, things improved. In the 1750s turnpike roads were introduced, allowing statutory bodies to charge tolls in return for their bit of road being maintained. By 1776 Stirling was ideal for Royal Mail coaches passing on their way from Edinburgh or Glasgow to Perth, which meant that carriage builders soon arrived to set up, offering repairs or rescuing coaches from the rougher tracks.

Edinburgh firm J Croall & Co owned a carriage-building works in Stirling until 1802. One of their apprentices was Henry Kinross who with William Croall founded Croall & Kinross Carriageworks. In 1820 they ran two stage coaches, ‘Soho’ and ‘Carron’. Soho was an elegant four-inside safety coach, an 1829 advert announcing it would run from Stirling “every lawful day, at Four o’clock, afternoon and leave Edinburgh every lawful morning at nine o’clock. One coachman throughout and no guard. Fares: Inside 8 shillings, Outside 5 shillings,” the latter being £14 in today’s money for the privilege of bouncing uncomfortably for some 30 miles, trying not to fall off.

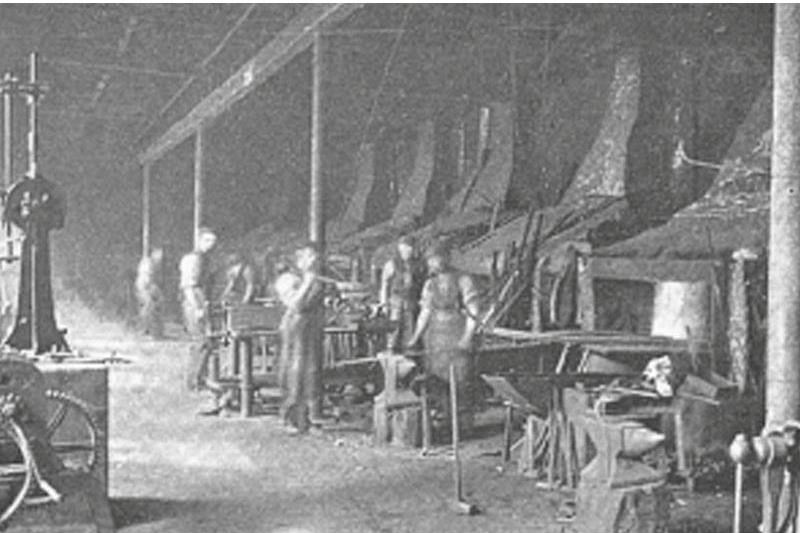

By now, the company was turning over £6,000 a year [over £400,000 today], according to the 1845 Statistical Account of Stirling, and “100 people were employed working 10 hours a day.” In 1837 it was wound up and Henry, now seen as Scotland’s leading coachmaker, took over and promptly received a Royal Warrant appointing him “coachmaker for Scotland to Queen Victoria.” People lined the streets when Queen Victoria and Prince Albert visited Stirling in 1842.

“On reaching the bridge at Stirling,” one local paper wrote, “the horses of the royal coach were changed, and the entourage was joined by several hundred men belonging to the local militia to escort Her Majesty through the town. Soon afterwards, Queen Victoria “ordered a Dog Cart for the Balmoral estate with space underneath the seat for her Skye terriers Gay Girl, Spot and Wat.” Not suggested by the name but the colourful dog cart was pretty striking.

This early coaching era was rarely without tragedy. Descendant Alastair Kinross writes touchingly on his family website about the precariousness of daily life. He is related to Henry Kinross through the second wife of his nephew William Kinross, Ann Marshall. “His first wife Janet was killed by a runaway farm cart,” Alastair tells me, “but she just managed to save her baby James by putting him on the tail-board.”

Henry died in 1845 and nephew William took over. In 1851 a fire destroyed their workshops and carriages, yet that same year the company still found time to promote itself, duly winning a silver medal for most improved omnibus design at the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace, which increased their orders. Aptly named ‘Victoria’, its body painted

in the Queen’s tartan, it was “sufficiently commodious for carrying 19 passengers inside,” the official catalogue wrote; “a large well on the roof, fitted up with ornamental glass and ventilators, also makes a comfortable seat for outside passengers…It is adapted for two or three horses abreast, with equalizing bars, so that each horse may have an equal proportion of the draught.”

In 1874 William Kinross died and his sons George and James took over, but an ominous threat would come. In 1896 a new law, called the Locomotives on the Highways Act, allowed “‘light locomotives’ – horseless carriages weighing less than 3 tons – to travel at speeds up to 12mph without the need of an attendant to walk in front carrying a red flag.” But there was still hope for carriages. In 1908 the Stirling Observer wrote, “the rivalry of the motor car has interfered considerably…but there is a fairly good amount of work going on.”

When George retired, James continued. But in 1921 Scotland’s last horse-drawn tram company ended. Not ready to give up, the canny Kinrosses started on a coach-built car and during the Second World War produced horse-drawn lorries and floats, whilst also becoming agents for Standard Motor Cars that made ‘The Flying Standard: Britain’s Wonderful New Car.’ Their brochure dismissing the past with ironic nostalgia: “Yesterday, the stagecoach and the galloping chaise represented the peak of comfort and speed to travel…” In some people’s eyes they still did.